“They came in battle array as conquerors,

And the dust rose in whirlwinds on the roads.

Their spears glitted in the sun and their pennants fluttered like bats.

They made a loud clamor as they marched with their coats of mail,

And their weapons clashed and rattled.

Some of them were dressed in glistening iron from head to foot.

They terrified everyone who saw them.

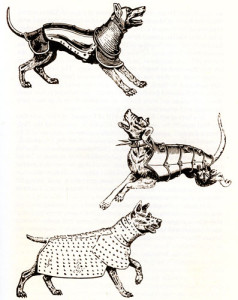

Their dogs came with them, running ahead of the column.

They raised their muzzles high; they lifted their muzzles to the wind.

They raced on before with saliva dripping from their jaws.”

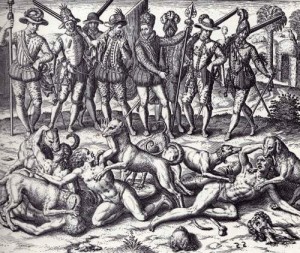

The epigraph, from which the title of Helena Maria Viramontes’ book, comes from The Broken Spears: the Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico, depicting the Conquistadors conquering the native Aztecs, intimidating them with their iron suits and vicious dogs. The title of the count, Broken Spears, derives from a phrase in the book, which was actually misinterpreted, actually meaning “broken bones”. However, I find the original title much more compelling, as it tells of a nation of Aztec warriors being conquered themselves. Their might, symbolized by their weaponry, is shattered; they simply become another one of the conquered. The Spanish translation (the original published version) bares another title: Vision of the Vanquished, which provides insight on the hopeless feeling of the conquered. I would like to explore the titles, as well as the rest of the epigraph, in relation to the novel.

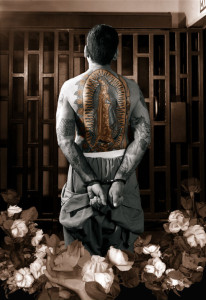

The novel opens with the people of Mexico being conquered again. Though they too were once warriors, of Spanish conquistador and Aztec blood, fighting to survive in East LA which is not only discriminated against by the upper classes and white majority, but is struggling with poverty and gang violence. In addition to this, they must now survive the quarantine and the authority figures that come with it. Cut off from the rest of the city and treated like inmates, they too have become unable to fight. While their spears were bending with the pressure of being a minority and of lower socio-economic standing, the dehumanizing effect of the quarantine authority was the final straw.

Their Dogs Came With Them is, in itself, “visions of the vanquished”. The novel carries an aura of hopelessness as we follow characters that seem unable to remove themselves from their bad situations. They are vanquished by the quarantine authority, but also by the forces in their personal lives: Ermila by her family and boyfriend, Turtle by the response to her abnormal gender identity, Tranquilina by her struggles with faith, Ana by her responsibility to Ben. This novel allows us to see the world through their eyes and feel the devastating hopelessness of being conquered.

I believe that the epigraph inspired not only the title, but also the entire novel. Assuming this is true, a closer look into the epigraph also gives nuance to the book and its characters. I believe one reading of the epigraph in the context of the book is that it alludes to the construction of the freeways. “The dust rose in whirlwinds on the roads” can be an allusion to the construction of the freeways and the rubble from its construction and in its wake. The spears and pennants of the warriors are machinery and the tape and blockades used to denote a construction cite. Their construction is “the loud clamor”. Their battle attire is hardhats. The conquerors “dressed in iron” can also be seen as the freeway, its grey concrete making it look like an iron-armored giant.

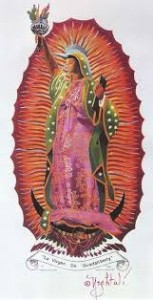

I believe the later half, in this instance, refers to the quarantine and the authority behind it. “Dressed in iron from head to foot” can also be seen as the steely persona of the QA, who are dressed in uniforms of white. Though the QA is there to kill the dogs, the dogs are used as a vehicle to cut of the East LA population from the rest of the city; in this way, I believe it is reasonable to say that they are “their” dogs. The saliva “dripping from [the dogs’] jaws” is reminiscent of the foaming of the mouth rabies causes.

The gravity of the epigraph of the Spanish conquest of Mexico lends gravity to the dividing and confining of East LA. Like the indigenous people, they are being made a lesser by a lighter skinned conqueror. Their community is dying from the unceremonious butchering caused by the freeways. They are dehumanized by the quarantine made to prohibit the spread of dogs with rabies; this, in a way, equates the people to dogs. “Any unleashed mammal will be shot.”

Sources:

Silverblatt, Michael. “Helena Maria Viramontes”. Bookworm. 16 Aug. 2007. http://www.kcrw.com/etc/programs/bw/bw070816helena_maria_viramon

León, Portilla M, and Lysander Kemp. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press, 1962. PDF found at: http://socialiststories.net/liberate/Vision%20of%20the%20Vanquished,%20or%20The%20Broken%20Spears%20by%20Miguel%20Leon-Portilla.pdf