As an active member of the first generation college student (hereby referred to as “first-gen”) community, I have come to see a lot of my expereinces through this lens. Before it used to be an unconscious observation, merely me living my life not really thinking or analyzing the course of events or the decisions I have made based off of this one area of identity. That is not to say that every decision I make now is because I am first-gen. On the contrary, I still rarely consciously look at the world through these particular glasses. But now I do take the time to analyze these decisions and experiences.

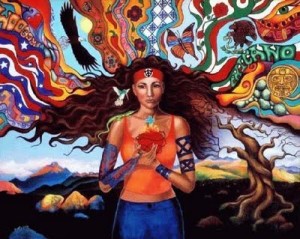

The Chicana aspect is a given for I am Chicana. My own culture and the way I embrace it finds its way into my work and shows my view as a Chicana student. What I really tried to focus in this project was the gothic perspective of being a first generation college student as seen through these expereinces that I have had within the last two years. Told in the form of diary entries, it is split into three parts (no particular order) and shall be posted in such way so as to mimic the old Victorian serialization publication method.

*************

April 4, 2014

A few days ago, I spoke on a panel for incoming Latino students. Not my first panel, and as a sophomore, I know it will not be my last. In the back part of my mind, I expected certain questions to be asked of me: what life would like on campus, how easy it would be to make friends, how long does it take to get over homesickness? (Surprisingly, since I was speaking in front of parents only, I still suspected these questions to be at the top of the list.) Of course, I cannot forget the one question that haunted even my mind as I was off trying to make friends at this potential school during my Latino Overnight: finances. As I sat down the table from my dad, I could feel his empathetic sigh when a parent asked him about how we pay for college. Memories of my freshman year—countless tears, staring at a screen displaying the 20k I had no way of paying off, and the constant praying that the number would just go away by some miracle of God—instantly replayed in my mind, not a fresh wound but more like an ever present fog in my life. I can always see the light and its end but it never fails to hover and remind me that I’m here but only through struggle.

It’s not a topic I’m uncomfortable with. I’ve constantly written about it—a small collection of my poems are dedicated to being forced to leave LMU, dollar billed shackles pulling down on my wrists as I walked off campus, guilt and shame bleeding into my eyes. But there is something about feeling the words come out of my mouth that leaves a foul taste. Like a coffee after taste; or how when you’re sick with enflamed tonsils, this post-hangover dry taste lingers in the back of your throat that you just can’t wash out no matter how many times you brush your teeth or gargle mouth wash. It’s a taste that I can never get used to and just want out. Even if I want to stay quiet about it, however, I know I can’t be. There are too many asking me to tell it. Too many people asking me how I did it.

I don’t know.

How do you explain the truth? That you have no idea as to how you managed to make everything happen. That it was by some miracle of God that I managed to find the money. That it was luck that an old settlement finally came in and that helped pay a good majority of my debt.

Yet, when those parents came up to me after the panel, asking me the age old question, How did you do it? I had to be honest.

It was a combination of luck and faith. Constant contact with financial aid. Here’s the number of my counselor. But don’t be disappointed if it’s not meant to be. It almost wasn’t for me.

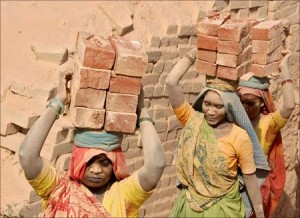

Money.

Money has always been the problem. I thought my financial aid package from LMU was one of the biggest. It covered three-fourths of my tuition; if I would’ve looked closer at my other packages, I would’ve chosen either Cal State Long Beach or UC Irvine. The numbers were smaller, but then again so was the tuition.

The concept of a private university won me over, though. Being able to say of how I went to this small, private university right after high school—it was a luxury, a privilege that I felt I deserved having pulled all the all-nighters in high school. Especially after Overnight. How could I say no to a community that made me feel like I was at home? To friends that were already imagining our first year together?

You can’t register for classes until you have paid off the semester.

I first asked my dad about payments in August. His response was simple: I am not paying for your school. I can’t afford it.

When I was younger I used to think that the ocean rumbled because it was screaming out of heartache. The ocean’s cry could not have overshadowed the way my heart started crying. The literal breaking I felt as I sat in the back of the car as I was getting dropped off at my dorm. I didn’t say anything else; stayed quiet as I took down my weekend bag filled with freshly done laundry.

It wasn’t until my parents left and my newest closest friend came in that I let the waves rumble on.

It’s not uncommon for first-gen students to face financial issues.

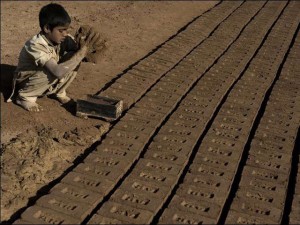

It was with two checkboxes that I started realizing that maybe things were going to be different for me in college. I remember in high school already starting to use the term “first-gen” as a part of my identity. It was going to be my gateway to scholarships and college in general. I embraced this. I embraced the “benefits” that I thought would come with accepting this identity.

I never thought of what it truly meant to be first-gen. I never thought of how other students might have knowledge that I didn’t. I never thought that maybe I was missing pieces to the puzzle. In my mind, I had figured it all out. All on my own. My own well-earned bragging right.

It’s why I held my head in shame. Why I hated that I let the situation get the way it was. Why it was hard for me to go to bed at night because of this constant migraine that I couldn’t shake off no matter what I tried. Why I ended up hospitalized for a few hours. Stress-related heart condition, the doctor had said.

I know, you really didn’t need to tell me twice.

No te preocupes, papi. Me salgo por el semestre. Regreso cuando la hora llegue.

It was right before my debt went to collections. I finished the online application. The words “Leave of Absence” blaring brighter than the lights of New York City. I could see the sympathy in my parents’ eyes. Later, I would learn how my dad felt like he had failed me because he couldn’t afford the school of my dreams.

Hi Genesis, my name is Linda Rojas*. My parents met you at Latino Overnight and said that you can help me. I love LMU and I want to go there with all my heart, but it’s the issue of financial aid. How did you do it?

Everyone assured me that I was making the right decision. That I wasn’t failing because I decided to take the leave. But that didn’t mean I felt content with my decision. I felt the detachment from my friends. I still kept in contact with them but that didn’t mean I didn’t feel left out on some level.

By the end of winter break, I could feel myself questioning my identity. I couldn’t help but think “if I wasn’t first-gen then this wouldn’t have happened.” How can I say that for sure? I have met students that are not first-gen yet they have also been faced with the same issue as me. It wasn’t just a “me” or “first-gen” issue; I just didn’t see it that way. The world was a vortex of me and my issues. The only ones that rang through to me were the ones tied to people from the same background or similar issues to mine.

It was my honest belief at the time.

Hi Linda. I’m going to be honest: luck was my captain, faith was my anchor. I’m going to tell you how to do this, at least how it worked for me. But please, if at the end of the day, you realize you can’t despite all the resources you have used, don’t feel like a failure. You’ll find yourself at the school you are meant to be at.