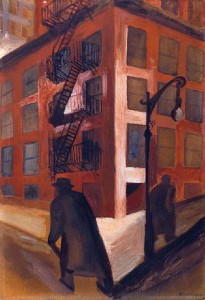

Take a drive around Los Angeles and you will see at least one wall mural throughout your city drive. Elaborate and colorful, or dark and ominous covering the wall of either a business or building. Wall murals throughout history have become an integral part of the Los Angeles community like with the mural above depicting the first phase of the Battle of Los Angeles by artist Teachalakazi. The wall murals presented in this article are from La Placita of Los Angeles. Today crowned as the beginnings of Los Angeles, it’s historical atmosphere, buildings and churches are considered one of Southern California’s most important landmarks.

Wall murals present themselves as free art full of meaning and empowerment for any individual. This individual in turn creates the community they live in becoming unified under the same social, political and cultural setting. “The walls that urban residents daily encounter are not merely structures containing and dividing space; they are also surfaces that become inscribed with different messages, which are read both figuratively and literally. The imperatives of many different groups contend and collude on these walls”(Kim,13). Many neighborhoods are created solely by the composition of its arts marking its historical establishments and therefore individuality. “The condition and appearance of the built environment in any given area becomes it’s public face, it’s facade, it’s most immediate aspect”(Kim,13).

The influence that wall murals create in a city go unnoticed, “Neighborhoods are not simply geographic units organized according to municipal design; they are also social, emotional, and stylistic environments. At the same time, while all individuals find themselves associated with groupings of people based on geographic proximity, economic class, ethnic classification, and social affiliations, all of us are involuntary participants in mass-generated culture”(Kim,8). By making wall murals of an informative nature it can in turn disintegrate false or negative social constructs leading to a unified community.

The involuntary participation that the individual goes through in engaging contact with a subject leads to awareness of an issue. We as people “…can’t dismiss the wide-reaching influence of the work produced by the idealistic and activist-minded Chicano artists of the 1960’s and 1970’s…in relation to el movimiento”(Kim,9). Wall murals played a big part in the Chicano movement by reaching a broad audience without giving directly personal political commentary.”Muralists, at their best, sought to use the semi-autonomous status of art-it’s aesthetic appropriation of the world such that the image stands in productive contradistinction to reality-as an allegory for political conduct”(Anreus,3).Murals have always created a powerful impact within every community they have been present in creating an opportunity for education and cultural knowledge. “Purportedly acting as mediators between “the people” and the state, as the “voice of the voiceless,” the muralists elaborated a legendary visual program remembered for lauding the worker, the Indian, and the peasant as active agents of national formation”(Anreus,13). In the wall mural above, we see the workers, Indians and peasants being presented as defenders of their rights. The leaders are in the front, holding the Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, in whose significance will be further detailed below, the Indian carrying what seems to be a bow and arrow, and the peasants running on the sides. Other than the main revolutionaries, the other figures who are seen as voiceless, are depicted as being empowered through a task of unity and urgency in revolting against injustices. The Battle of Los Angeles, the colorful trompe l’eoil above, covers relevant subject matter to the city of LA marking important events of the era that the city was established. “Graffiti and murals implicitly and explicitly record public and personal events and messages”(Kim,52). In the Battle of Los Angeles the revolutionaries, Jose Maria Flores, Jose Antonio Carrillo, and Andres Pico, are marching through the plaza in a depiction of what is known as the first phase of the Battle of Los Angeles. Jose Maria Flores was the military commander of the uprising (Wikipedia). One of the revolutionaries is holding the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, who is and has been an essential figure since her apparition to Saint Juan Diego in 1531. Peter Quezeda, a Chicano wall muralist explains her importance, “The image of Guadalupe [has been] chosen because she is a popular and respected figure among many Mexican Catholics. A particularly Mexican manifestation of the Virgin Mary and the patron saint of Mexico, she is revered for her clement nature. Her image has also been evoked in revolutionary contexts both in Mexico and in the United States: by Father Hidalgo in the 1810 uprising against Spanish colonial rule of Mexico; by Zapatistas during the Mexican Revolution; and by the United Farm Workers under Cesar Chavez. The image of La Virgen de Guadalupe is also often used in gang and prison contexts in both tattoos and commemorative murals”(Kim,20). Her image brings years of historical struggles and endurance to empower those who need guidance or have been oppressed. Placing emphasis on Our Lady of Guadalupe in a mural not only symbolizes cultural identity but cultural history as well.

It is also important to mention one of the most influential and controversial wall murals, amongst the many, that Los Angeles has had, attracting attention to muralism in the city. “Sometimes called the “mural renaissance” or “the new mural movement,” these public art activities were inspired by educational murals commissioned by the Mexican government following the revolution of 1910 and then by the United States government under the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the 1930’s”(Kim,15). The Great Depression led to many projects in efforts to employ hundreds of unemployed individuals, 49 percent alone went towards the fine arts, leading to vital national sentiments that thrived the arts. In 1932, the wall mural of Siqueiros’ Tropical America was commissioned as part of these efforts in enhancing Los Angeles. David Alfaro Siqueiros was one of the Big Three or Los Tres Grandes, which include Jose Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera, of Mexico’s muralist movement. In the 1920’s and 30’s “The unstable political situation in Mexico, the lack of a developed art market, artists’ need for a living wage, and the desire to participate in international aesthetic debates prompted all three muralists to bring their production north of the border”(Anreus,210). Siqueiros’ Tropical America was essential in empowering the Chicano Movement. “Many Chicano and Chicana artists situate Tropical America in “the cultural nationalism of the Chicano civil rights movements of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s”: still, its legacy in California and, as radical public art, in the United States entails Siqueiros’ efforts to reshape the spatial politics of Los Angeles and urban geography in general”(Anreus,218). Tropical America is important in understanding Chicano muralism because it was a work that pioneered other murals of the time with it’s subject matter confronting a political and social matter through messages in its images.

In the images below we see Our Lady of Guadalupe between the Mexican flag and the American flag, along with flags of many other nations on the top, representing political unity and promoting cultural integration. The words that are written on the mural are “No estoy yo aqui que soy tu madre?” and “Am I not here who am your mother?” with “Reina de Mexico y Emperatriz de America” above the figure of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The meaning of this bilingual message is related to being a nation under the protection of the patroness of the Americas. In this mural two predominant communities of Los Angeles converge to take an empowering stance against man-created divisions. “In the late 1960’s, artists in several major cities sought to make their work more socially relevant and immediate to the lives of the “community”. By “community,” these artists were referring to neighborhoods or groups of people that had traditionally been underserved by the arts establishment. Influenced by concurrent movements for civil rights and social justice, many artists considered murals to be a powerful vehicle for social change and empowerment”(Kim,15). The mixing that has occurred for many years in the southwest lands are predominant themes in the Guadalupe mural bringing the two cultures together forming the perfect example of a Chicano wall mural. As a statement in the Chicano political movement the wall murals reflected political and social awarenesses. “A prolific force in this mural renaissance were artists and individuals of Mexican descent, who identified themselves as Chicanos to indicate their political consciousness. From 1965, Chicanos were involved in a relatively cohesive effort for advances in their civil rights. Referred to as el movimiento or la causa, these efforts sought improvements in education, work conditions, and political representation. Central to these efforts was the assertion of Chicano identity in ways that would convey cultural dignity according to their own terms, sensibilities, and history. Chicano artists were instrumental in the dissemination of visual presentations of this empowerment. These artists deliberately selected and elevated specific aspects of Mexican history and culture as a means of countering the negative stereotypes. In order to recognize the everyday expressive life of the entire community, images and styles were drawn from religion, traditional folk arts, and vernacular graphics, as well as from the creative expressions of youth, gang, and prison cultures”(Kim,15). The images on the wall mural of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the flags of the United States and Mexico and the mountains in the background capture many relevant elements to daily life in Los Angeles. “Artists collaborated with individuals in neighborhoods to produce murals with topical themes and images drawn from daily life”(Kim,15). The images in this wall mural are revered and very relatable to everyone in its community.”As such, mural painters aspired to bring the critical energies and utopian aspirations of the aesthetic realm to bear on the realm of the political in order to prompt public debate on interpretations of the nation and the contours of citizenship”(Anreus,2). This exchange of ideas and ideals encourage needed discourse bringing political and social issues to the forefront of the peoples agenda. “Murals that cross geographical and cultural boundaries, conceptual frameworks, political and racial divides, and imagined communities necessarily spark-and may even embrace-discussion and debate”(Anreus,223). The wall mural of Our Lady of Guadalupe between the American and Mexican flags, as well as the flags of other countries, bring peace and unity to all nations under the same common goal of prosperity and faith.

Works Cited

Anreus, Alejandro; Folgarait, Leonard and Ade, Robin. Mexican Muarlism: a critical history. Berekley: University of California Press, 2012. Print.

Kim, Sojin. Chicano Graffiti and Murals: The Neighborhood Art of Peter Quezada. University Press of Mississippi, 1995. Print.