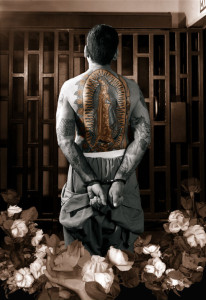

In the first part of my examination of the Lady of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), I examined the origins and history of where she emerged from and how her placement shaped Catholic and Mexican tradition. Her original interpretation was one of a loving and forgiving mother and I want to take that symbol and show the evolution of how she became one of revolution and action to people in transition themselves. She was first established as a symbol outside of the association of non-Indian Mexican population but in this part, I will be showcasing how that image of the Virgen represented and shaped the Chicano Movement as an emblem for their liberation, beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the 1960s. Her presence began as a religious figure (Part One) but now her image defies boundaries, not only appearing to the masses in religious institutions but now has evolved into a symbol of cultural identity displayed in murals, statues, paintings, and personal tattoos as a growing image of cultural and personal identity to the Chicanos living in the United States. Individual statements of selfhood, pride and expression such as public and private art forms, body tattoos, burials, household shrines, taxis, and memorabilia utilize the Virgen’s strong and poignant image as their grounded message of discovery. First and foremost, I think it is important to get a clear and underlining definition of what it means to be a Chicano. One of our very first assignments in class was personally defining what a Chicano is and we took to Twitter to define it. The definition I ended up with was:

Chicano/a is defined as pride in cultural identity wrapped up in social and political empowerment as a minority representation. #CHST332

By defining Chicano, I realized that is was a self-selected term that Mexican Americans choose to identity themselves with that encompasses a duality of recognizing Indigenous Mexican roots but also American identification. The term can also be used as a derogatory term to immigrants of Mexican heritage. The Chicano Movement gained momentum in the 1940s and 50s in two politically charged legal victories. Blacks and Chicanos during this time had many commonalties in the fight for civil rights in the 1960s living as minorities in the United States. One step in the fight for civil quality followed the popular Brown Vs Board of Education Case, and it was called Mendez Vs Westminster Supreme Court which abolished the notion of segregation of Latino children in white schools. In both cases, the Court deemed the segregation of Blacks and Latinos unconstitutional. In another case, Hernandez Vs. Texas, protection was guaranteed not only to blacks and whites, but another ethnicities in the United States under equal protection (Nittle). These smaller victories gave strength and pride to the Chicano Movement, as well as paved the way for more changes in the 1960s and 70s. The result of these later movements included organizing a union called the Union Farm Workers for rights of laborers in the fields, and the passing of the Equal Opportunity Act of 1974 which gave more bilingual school equational rights to children. The civil rights of Hispanics gained momentum by the organization of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund in 1968. Chicanos even formed a political party called the United Race, La Raza Unida, which mirrored the Black Panther Party (Nittle).

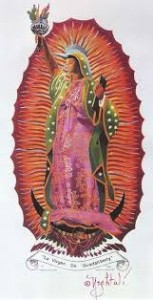

All of these movements gave not only political identity and power to the Chicano name but also a growing cultural identity to its people. This is where the image of the Virgen de Guadalupe comes into play as a universal icon of “passion and fervor” who appeared to Don Diego in the 16th century “as a Mestiza herself, dark skinned like most of the people in Mexico” (Prendez). The description and image of her dark skin is extremely vital to the importance of her representation of the Chicano people and their movement for equality in the United States. She became the patron saint of the Mexican people. Her image was used as a visual representation of the fight for independence in Mexico and the farm workers struggle in the 1960s. Her presence is widely regarded as one of the most recognizable and most used images in Chicano art.

Today, the Virgen has been a leading incorporation into “nationalist liberation struggles”, specifically in the Mexican independence from Spain, the Mexican Revolution and the Chicano Movement (Elenes 104):

“The timing of the event, the language she spoke, and the race of the Virgen are all significant because they signal recognition of the subjectivity of the indigenous and mestiza/o inhabitants of Mexico” (Elenes 104).

There have also been numerous examinations by Theologians on why the Virgen became such a iconic symbol in Latin American culture and specifically the human rights movement of the 1960s in Chicano nationalism: “At the forefront of these theological works on Our Lady of Guadalupe is the work of prominent Mexican American theologian Virgilio Elizondo. In Elizondo’s work, the driving theoretical lens is mestizaje (the Aztec and Spanish political, cultural, religious, and ethnic mix). As mestizos, Elizondo argues, Mexicans are not “either/or,” but “both and.” Therefore, the point of departure of Elizondo’s theological work on Our Lady of Guadalupe has always been the lived experience of people who exist at the intersection of two ways of knowing” (Castaneda-Liles)

This is a perfect transition into the third and final part of my examination into the Virgen de Guadalupe and her effect on feminism in the Chicano/a community. In part three, I will examine her role in allowing women of Mexican culture to speak for the masses through images of the Virgen and how she embodies their struggle for identity through epistemological meanings.

Works Cited

Elenes, Alejandra C. Transforming Borders: Chicana/o Popular Culture and Pedagogy. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2011. Print.

Nittle, Nadra Kareem. “The Chicano Movement: Brown and Proud”. Chicano Movement- History and Goals of the Chicano Movement. N.d. Web. 16 April 2014.<http://racerelations.about.com/od/historyofracerelations/a/BrownandProudTheChicanoMovement.htm>

Prendez, Jacobo. “In Defense of Chicano Art”. Thesis. N.d. Web. 16 April 2014. <http://students.seattleu.edu/clubs/mecha/chicanoart.html>

Castaneda-Liles, Socorro. “Our Lady of Guadalupe”. Our Lady of Guadalupe-Latino Studies- Oxford Bibliographies. N.d. Web. 16 April 2014. <http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199913701/obo-9780199913701-0043.xml>

Images:

http://www.bustedhalo.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/dupre-encountering_mary-Guadalupana_Delilah-Montoya.jpg

http://www2.sacurrent.com/news/story.asp?id=57675

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicano_art_movement

I can definitely see the Virgin as a symbol of native Mexican pride and also as a guide through the Chicano efforts to become respected members of American society. Guadalupe represents a harmonious mixture of the Spanish and aboriginal aspects of Mexican culture; therefore, she is the perfect emblem for the first and second generation of Mexican-Americans who are inspired by and also trying to maintain a sense of ancestral and national pride. Moreover, I always saw this particular apparition of the virgin, with her dark skin and her decision to speak for the disenfranchised, as a sort of advocator for the underdog, for those who are easily ignored or oppressed. The power she invests in Juan Diego, a simple but diligent man, gives them an agency and authority he and other humble peasants like him did not have. I can see how this motivation to stand up to the established system and proclaim the importance of marginalized peoples was adapted by the Chicanos who hoped to do just that, gain the respect and rights they deserved.

I think that Chicanas/os continue to use Guadalupe’s image because her image has been in many of Mexico’s movements. The image of La Virgen de Guadalupe has always been on the side of the oppressed. Examples of this would include Mexico’s Independence from Spain and Mexico’s Revolution. Like Mexicanos, Chicanos feel that La Virgen de Guadalupe will be there to help. This is why they keep her image close to them during movements such as the Chicano movement, the UFW boycotts, and in the present during protests to support an Immigration reform.