Dia de los Muertos also known as the Day of the Dead is a traditional “festive and colorful celebration of the Mexican and Latin American holiday” (Diaz, 77), which typically occurs from October 31st through November 2nd. “Almost unheard of in the United States 35 years ago, Day of the Dead, or ‘‘El Dia de los Muertos,’’ has become an annual autumn ritual in…families, schools, community centers, and museums around the country” (Marchi, 932). As a matter of fact, “El Dia de los Muertos, “Initiated in California in 1972 by Chicano artists who were inspired by Mexico’s Dia de los Muertos rituals, US expressions of the celebration, which center around public altar exhibits, emerged as part of the multi-faceted Chicano Movement” (Marchi, 932). With regard to the cultural significance of Dia de los Muertos in the Latino/a-Chicano/a communities, Marchi further notes “Many universities observe the celebration as part of Latino Studies, Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, Religion, and Spanish classes. Hundreds of art galleries across the United States, including prestigious museums such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian Institute, hold Day of the Dead exhibits, while growing numbers of municipal governments and civic organizations sponsor Day of the Dead festivals…” (Marchi, 932). One of the main rituals that people practice when celebrating Dia de los Muertos is the construction of altars. Altars play a significant role in remembering and honoring departed souls (family members, friends, and other significant people). Some of the offerings people place on Dia de los Muertos altars include but not limited to are sugar skulled shaped candies (calavaras), pictures, candles, statutes of the La Virgen de Guadalupe, among other saints, homemade food, Pan de Muertos, alcoholic beverages, water, and flowers, among other items, which have symbolic meaning. In celebrating Dia de los Muertos for the first time, I have chosen to construct an altar to honor my grandpa, Frank Cortez. In this essay, first I detail my grandfather’s biographical information and family structure. Second, I discuss the reasons why I have chosen to honor my grandpa for this altar project. Last, I discuss the significance of each item that I placed on his altar.

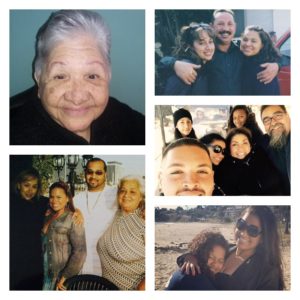

To start, I want to detail biographical information about my grandpa, Frank Cortez. My grandpa was born on April 2nd, 1931 in Los Angeles, California to his parents Guadalupe and Cristina Cortez. Both of his parents were born in Mexico, however migrated to the United States in 1919 and settled in Venice, California. I do not know too much about my grandpa’s childhood, however, my mom says that he identified with both his Chicano and indigenous heritage. My grandpa and grandma married on March 21st, 1955. Together they had ten children, seven boys and three girls. In terms of his occupation, he was a truck driver for Long Shore Pumping Company for many years, a very hardworking man-the sole provider of the home. On several occasions my mother has remarked how hard he worked to maintain a “roof over the family’s head and food on the table.” Similar to Carlos and Juan in the article on “Masculinity Reconfigured: Shaking up Gender in Chicano/Latino Literature” my grandfather “provided the basic necessities like food, clothing, and shelter for my grandmother and children” (Martinez, 108). The structure of my grandparent’s family is similar to the patriarchal structure of the Chicano family. My grandfather, the patriarch, was the breadwinner and provider “raised in traditional ways of life, …in which it is habitual for males to perform the role of leaders in their families” (Martinez, 106). My grandmother, on the other hand, who is a traditional Mexicana born in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, Mexico, was “…relegated to the tasks of homecare and child rearing” (Trujillo, 190). In short, my grandmother’s sole purpose in the home was to cook, clean, and take care of “la familia.” She was “the true backbone of the familia” (Trujillo, 189). Given that my grandparents adopted traditional Chicano/a male and female gender roles in their household, my mom, tios, and tias perpetuated the same gendered roles. The boys took on the male gender roles, which included taking out the trash, mowing the lawn, and picking the weeds and maintaining my grandmother’s beautiful garden; while the females helped my grandma make breakfast and dinner, do laundry, iron clothes, and clean the house (mop, sweep, clean dishes, etc.). To be honest, my grandpa did not want my grandmother to work; he wanted her to take care of their children and home, while he provided the means necessary to survive.

Although my grandparent’s family structure is similar to the traditional Chicano family in terms of gender roles, my grandfather, according to my mom, did not take on the “…the stereotypical machista that drank heavily, gambled, got into fights, and had affairs with other women…” (Martinez, 108). In other words, my grandfather was not hyper-masculine or a machismo. Unlike Sofia’s husband Domingo in the book So Far From God, my grandfather never abandoned his family or gambled the deed away to their home (Castillo, 1993). In fact, my grandpa is the one who bought my grandmother a piece of land; the home where she currently resides, something many Chicanos struggled to do in the late 1950’s. To tell the truth, my grandfather was always there for his family, he made the best of their working class lifestyle. More importantly, my grandpa treated my grandmother and the rest of the family with respect and dignity. In all honesty, my mom says that my grandpa catered to my grandma like a queen. As a matter of fact, he handed his weekly earnings to my grandma every Friday, something “machistas” rarely do in the Chicano family structure. Above all, on several occasions my mom has echoed how respectful, loving, caring, humble, and giving my grandfather was-my grandmother, his children, and grandchildren, were his world. At any rate, my grandfather was an excellent husband, father, grandfather, and provider, whose life ended on April 22nd, 1982 due to acute heart failure and diabetes. He was only 51 years old when he died. In sum, “he was the glue that held “la familia” together!”

Because my grandfather was the glue that held “la familia” together, I chose to make an altar to remember and honor his life. I chose my grandpa because he has played a significant role in shaping my mom’s perceptions about life. Although my grandfather instilled important values in all of his children, my mother, especially, takes on many of his impactful characteristics. All my life, I have heard my mom admire my grandpa’s work ethic and loyalty to his familia. Despite the fact that my memory is blurred when it comes to my grandpa’s legacy, I see many of his characteristics in my mother. Some of the characteristics my mother learned from my grandpa include, having a good work ethic, honesty, loyalty, respect, dedication, dignity, perseverance, compassion, humility, and to be loving. Without these characteristics, I do not believe my mom would have survived many of the challenges she has encountered in her lifetime (domestic abuse, single mother of three, and sole caretaker of my grandmother and disabled uncle). Similar to my grandfather, my mom sacrificed everything for our happiness-we never went without. “…Her strength and self sacrifice continues to keep our family going” (Trujillo, 189). My mother is one of the hardest working women I know who has dedicated her whole life to making sure “la familia” is taken care of physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually. For this reason, I am grateful for my grandpa’s existence as an excellent father and male role model in our family. He has raised one of the strongest and independent women I know, my mother. In fact, my mother has passed down many of my grandpa’s characteristics to my daughter and me. If it weren’t for my mother, I wouldn’t be half the woman I am today-a loyal and dedicated hardworking person. As a result, I have chosen to make an altar in my home to welcome my grandpa’s spirit. In welcoming my grandpa’s spirit, I want him to know how grateful I am for teaching my mother the core values that make her the strong person she is today.

Making altars is a part of the Dia de los Muertos tradition widely celebrated in many Latino/a-Chicano/a families. However, my family does not participate in this tradition. Instead, my family visits my grandpa’s gravesite at the cemetery. Typically, the visits take place on holidays (Christmas, Thanksgiving, Easter) and his birthday. Usually, my family place flowers on his grave after wiping it down with a rag and Windex. Once this is done and everyone is settled, my family sits around his gravesite and tells stories acknowledging some of my grandpa’s precious moments. Some family members laugh, while others weep. In addition to reminiscing on past times, my family also brings a radio cd player to play my grandpa’s favorite music. However, over time, my family stopped making this tradition a priority. Little by little, family members stopped participating in the family gatherings. Despite this reality, my mom, my siblings and me still make it a part of our life- we still visit my grandpa’s gravesite annually.

Although my family and I have never recognized Dia de los Muertos as one of our family celebrations or traditions, it is obvious that our customs are very similar to this idea of “honoring and remembering the deceased.” The only difference is that we never built an altar in our homes to honor my grandfather. Instead, we visit his gravesite. However, now familiar with Dia de los Muertos and why people in the Latino/a-Chicano/a communities construct altars, I have chosen to make my own Dia de los Muertos altar to honor my grandpa. To celebrate and honor my grandpa’s life, I have added different items on his altar, which represent some aspect of his legacy. Some of the objects that I placed on his altar include, one of his favorite record albums, mariachi toy, candy bar (Snickers), tequila shot glass, a toy truck, low rider car, bean and cheese burrito con chile, pictures, Virgen de Guadalupe statues, rosaries, candles, skulls, bones, and skeletons. The record album on the altar symbolizes one of his favorite records by Little Joe’s Latinaires. He dedicated a song called Por Un Amor to my grandmother before he passed away. In addition to loving the song Por Un Amor, my grandpa also loved Volver, Volver by Vicente Fernandez, which is the music playing in the video presentation of my altar on YouTube. Aside from music, I also placed a mini mariachi figure on the altar. Since my mom has told me stories about how my grandpa paid mariachis to serenade my grandmother with love songs when they went out for dates on Friday nights, I thought he would appreciate this. I also placed a snickers candy bar on the altar, as they were his favorite type of candy bar. Furthermore, I placed a tequila shot glass on the altar to represent the fact that he loved to have drinks on Fridays after work. Every Friday, my grandfather and grandmother went out for drinks and to dance the night away. My mom says that my grandpa and grandma loved dancing, especially salsa and cumbias. In addition to the tequila shot glass, I also placed a toy truck on the altar to represent his occupation and work ethic. Because he was such a hardworking man, I felt compelled to honor his work ethic. Moreover, I included a low rider car, as he loved classic cars. My mom says that he went to low rider car shows a couple times a year. In fact, he owned a low rider car. Because he loved bean and cheese burritos with chile, it was only fitting to add this dish to his altar. My grandmother says that, “He loved his burritos.” She used to make homemade tortillas, chile, and beans every morning for his breakfast and lunch. Besides food, I added some of my grandpa’s photos. The black and white photo of my grandpa and grandma featured on the center of the altar is one of my grandpa’s favorite photos. On this night, they were out having drinks and ready to dance the night away. I also placed La Virgen de Guadalupe statutes and rosaries on the altar to symbolize the Catholic faith my grandpa followed. Last, as a form of décor, I placed candles, skulls, skeletons, and bones on the altar. By creating an altar with all of these offerings for my grandpa, I welcome his spirit with open arms. I want him know to that he is not forgotten, that his influential spirit lives on in many forms (stories, individual memories, scent of certain foods, specific activities and holidays, and certain songs).

Works Cited

Castillo, A. (1993). So Far From God. New York: W.W. Norton &Company, Inc.

Diaz, Shelley. “Dia De Los Muertos.” School Library Journal 61.8 (2015): 77. Academic Search Premier. Web. 27 Nov.2016.

Marchi, Regina M. “RACE and the NEWS: Coverage of Martin Luther King Day and Dia De Los Muertos in Two California Dailies.” Journalism Studies, 9.6 (2008): 925-944.

Martinez, Pablo. E. “Masculinity Reconfigured: Shaking up Gender in Chicano/Latino Literature.” Divergencias. Revista de estudios linguisticos y literarios. 10.1 (2012): 106-15. Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

Trujillo, Carla. “Chicana Lesbians Fear and Loathing In The Chicano Community”, in Chicana Lesbians, Carla Trujillo ed. (Berkeley: Third Woman Press, 1991), 187.