Feminist have reinterpreted Our Lady of Guadalupe to better relate to her. Sandra Cisneros describes this reinterpretation in her essay, “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess.” Cisneros speaks from her own experience of her alienation toward her own body. During her early years up until she went to college she was taught that anything having to do with her private body parts were to remain private. She stresses that her religion and culture “helped to create that blur, a vagueness about what went on ‘down there” (Cisneros, 46). Traditionally Catholicism and the Mexican culture have always pushed women to cover up their bodies. Similarly in a note in “Little Miracles, Kept Promises” from the collection of short stories in Woman Hollering Creek, Cisneros creates Chicana character named Chayito who comes to express her developing relationship with Our Lady of Guadalupe.

First it’s important to know that Our Lady of Guadalupe is the patroness of Mexico and who symbolizes virginity. She appeared to Juan Diego at the hill of Tepeyac and asked him to deliver the message to the bishop that she wanted the construction of a chapel there. She appeared on his cloak as proof of her miracles when he was delivering the message to the bishop for the third time. Our Lady of Guadalupe continues to be a significant force of devotion among women from Mexican descent and other parts of what is known as Latin America. She is traditionally superficially depicted as mild and submissive in relation to her virginity; the embodiment of what a woman should be like. Chicana feminists like Sandra Cisneros have re-imagined Our Lady of Guadalupe to describe their evolving relationship with her.

In “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess,” Cisneros describes her experience of silence and says, “[i]f I was a graduate student, was shy about talking to anyone about my body and sex, imagine how difficult it must be for a young girl in middle school or high school living […] [with] no information other than misinformation from the girlfriends and the boyfriend” (48). This experience is replicated among many other Latinas who grow up in a traditional household and whose bodies are kept in silence. The culture keeps demanding young women to not get pregnant but nobody ever sits down to talk about how to keep from getting pregnant, the only choice young women have is to listen to the misinformation that is out there. Cisneros continues to state, “[t]his is why I was angry, for some nay years every time I saw la Virgen de Guadalupe, my culture’s role model for brown women like me […] [d]id boys have to aspire to be Jesus? I never saw any evidence of it” (Cisneros, 48). She is relating the culture oppression against young women as sexual beings as a result of Our Lady of Guadalupe’s submissiveness.

In “Little Miracles, Kept Promises,” Chayito begins her short story (or note) speaking to Our Lady of Guadalupe as she is pinning the part of her hair she cut off. She describes the ways in which the patriarchal structure continues to humiliate her for not abiding by the social standards of how a girl is suppose to act. She states, “Virgencita de Guadalupe. For a long time I wouldn’t let you in my house. I couldn’t see you without seeing my ma each time my father came home drunk and yelling, blaming everything that ever went wrong in his life on her” (Cisneros, 127). In her eyes Our Lady of Guadalupe only symbolized a sufferer, someone who would take everything in and not fight back just like her mother took her father’s verbal abuse. Chayito could not stand to see the pain her mother and grandmother underwent as women. She wanted to see Our Lady of Guadalupe “bare-breasted, [with] snakes in [her] hands […] leaping and somersaulting the backs of bulls” (Cisneros, 127). Chayito wanted to see Our Lady of Guadalupe as a woman who had breasts, who felt confident with her body; a woman who could take anything even a bull and who showed no fear. Just like Chayito wanted to see Our Lady of Guadalupe bare-breasted, in “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess,” Cisneros states, “I want to lift her dress as I did my doll’s and look to see if she comes with chones [underwear], and does her panocha [vagina] look like mine, and does she have dark nipples too?” (Cisneros, 51).

Placing both readings side by side, we see that Cisneros used Chayito’s voice to demonstrate her grappling’s of relationship with Our Lady of Guadalupe, especially when she says, “When I look at la Virgen de Guadalupe, she is not the Lupe of my childhood […] She is Guadalupe the sex goddess” (Cisneros, 49). In “little Miracles, Kept Promises” Chayito comes to realize that Our Lady of Guadalupe is “[n]o longer Mary the mild […] That you could have the power to rally a people when a country was born […] made me think maybe there is power in my mother’s patience” (Cisneros, 128). Both demonstrate the relationship to Our Lady of Guadalupe as empowering, one being able to embrace her sexual being and the other the strength that women possess within.

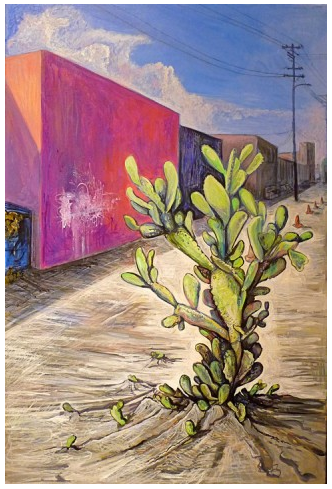

Reinterpreting Our Lady of Guadalupe as Sandra Cisneros has in “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess” has caused controversy especially among people who are religious in the traditional ways. In order for Chicanas to be able to connect with her and see her as an empowering figure they have had to re-imagine her as someone who is just like any ordinary woman. This is specifically important to Chicanas because of the history of colonization and conquest that the indigenous population endured as the Spanish conquerors took over Mexico, central and south America.

Additional Resources: