When I first started reading this play, I was intrigued by Chac-Mool’s name. I thought to myself that this name must have a special meaning behind it. I thought, maybe a God. However this is not the case.

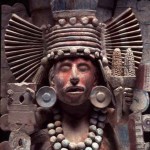

The statue of the Chacmool was first found in 1875 by Augustus Le Plungeon. After this, many other Chacmools were found throughout Mexico. “The earliest examples date from the Terminal Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology (c. AD 800–900). Examples are known from the Postclassic Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, from the central Mexican city of Tula and from the Maya city of Chichen Itza in the Yucatán Peninsula.Further examples are known from Acolman, Cempoala, Michoacan, Querétaro and Tlaxcala” (Wikipedia). The Chacmool was used during sacrifice rituals. It is believed by archeologist that Chacmool was used as an offering table. Food such as fruits, tortillas, and tamales were placed on his plate. Another theory is that the heart of a person being sacrificed was placed on the plate held by Chacmool. Chacmool was known as an intermediary between humans and the Gods. As I was reading Hungry Woman A Mexican Medea by Cherrie Moraga I kept in mind what Chacmool meant to the indigenous people of Mexico.

Medea didn’t want to let go of Chac-Mool. Medea might be viewed as a selfish woman who was only thinking about herself. In act two, scene four, there is a conversation between Chac-Mool and Medea. Medea and Chac-Mool argue about him going away to Aztlan with his father, Jason. Medea feels that because he is a man, Chac-Mool will be ruined by manhood.

Chac-Mool: I want to be initiated, Mama.

Medea: You want to cut open your chest?…(Grabbing a letter opener from the table) Then start your initiation right here…Cut open your mother’s chest first! Dig out her heart with your hands because that’s what they’ll teach you, to despise a mother’s love, a woman’s touch–

Chac-Mool: I won’t do that.

Medea: You say that because you’re still young. Your manhood, the size of acorns. When you feel yourself grown and hard as oak, you’ll forget.

Medea feels that once he becomes a man, Chac-Mool won’t love her the same way, especially if he moves out with his father. Medea feels as though she is going to be “sacrificed” by her own son. This made me think about Chacmool, the statue because hearts were placed on his plate. Medea feels as if her son is going to rip her heart out. Because of this, Medea decides to sacrifice her son instead. I find it ironic that Medea called her son Chac-Mool and later on sacrifices him, since in indigenous culture Chacmool was the warrior who sacrifices were placed on.

“Chacmool.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chacmool#Dating_and_origin

Moraga, Cherríe, Irma Mayorga, and Cherríe Moraga. The Hungry Woman. Albuquerque, NM: West End, 2001. Print.

Image: http://www.fuertedesandiego.inah.gob.mx/images/stories/salas_permanentes/salas_arqueol/maya/original/21chac_mool