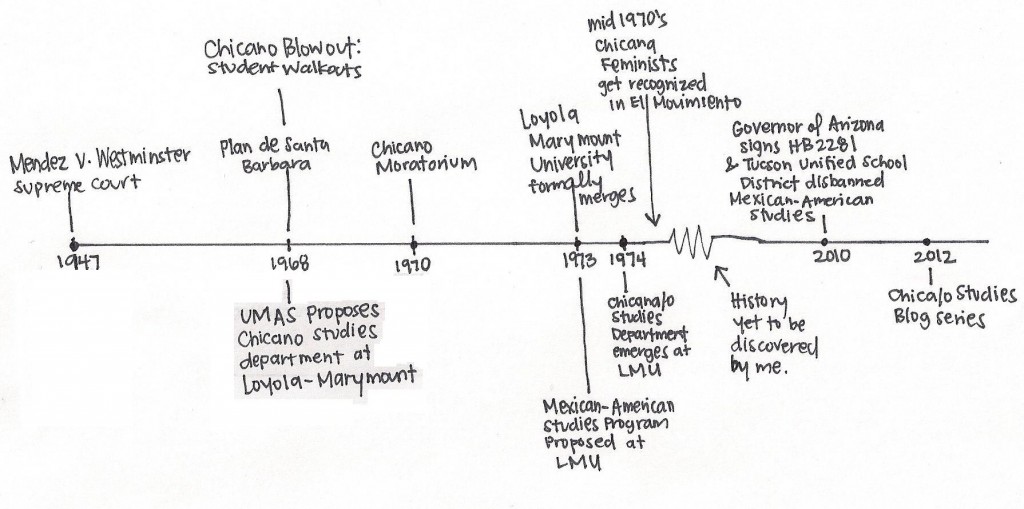

This is part of a longer blog series, which you can find links to the previous as well as the next blog posts at the bottom of this blog.

Back in 1968 the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) of Loyola-Marymount presented a proposal for the development and implementation of a Chicano Studies Department on nothing more than white paper and a typewriter. But after looking in the Chicana/o Studies Department’s archives in the University’s Archives found in the library’s Archives and Special Collections, I found a very interesting document. I found the Mexican-American Studies Degree Program description.

Back in 1968 the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) of Loyola-Marymount presented a proposal for the development and implementation of a Chicano Studies Department on nothing more than white paper and a typewriter. But after looking in the Chicana/o Studies Department’s archives in the University’s Archives found in the library’s Archives and Special Collections, I found a very interesting document. I found the Mexican-American Studies Degree Program description.

Finding this document comes at a shock for many reasons. One of which is simply at just looking at this document versus the proposal presented by UMAS. One of the big visual differences include the letterhead this document has. Not only does it have an official Loyola Marymount of Los Angeles letterhead but it also has a sort of seal for the program itself. This shows us that this document although not stated anywhere is not brought up by the students.Through its presentation, we know it means business because it is a formal document that a faculty or even staff member might of worked on.

Aside from the way it looks, the language used is sophisticated and formal. It does not present an attitude or voice like the UMAS proposal did, to the contrary it presents itself very politically and states its desire in a way that it remains neutral yet confident in what it wants. The only thing that is left unclear though is what gave rise to this and why did it take 5 years for it to appear, as this document is dated from February 14, 1973. Since for the moment those questions remained unanswered we can review it so as to share its contents and try to answer the questions.The document is comprised of 5 different areas. It starts of with the rationale behind the program, then continues into the proposed program of studies which is followed by the class list for humanities and social sciences and ends with the costs of the program.

The rationale begins by first stating the demographics and then gives points as to why the program is vital to an university education. The author behind the document brings the reader’s awareness around the issue that there exist irrelevant issues to the minorities of color, which includes the nation’s second largest minority, the Mexican-Americans. A minority whose unique situation “necessitates academic attention from interdisciplinary perspectives” which would encompass analysis of their historical, social, economical, psychological, cultural and political aspects. It continues on by stating that a degree in such a program not only would develop a student but also “fulfill one of the most important goals of Loyola University” as stated by Father Merrifield in his address on the goals of liberal education which says that there must exist an understanding of social -political realities and awareness of and sensitivity to the deep social problems in America. At the core of it stood the University’s goal to serve the community which included the presence of the largest population of Mexican descent outside of Mexico City and Guadalajara, including the presence of Mexican-American students whose presence is eluded from the 11% of Spanish surname population at Loyola. (Only to be compared to the approximate 21% currently found now at LMU.) These students need to be well prepared to pursue advanced degrees and strong foundations that a degree or double degree in Mexican-American Studies would provide them with.

The preparation would be coming from the proposed program of studies that included a focus on humanities and social sciences. The proposed program required the student to either take or test out of Spanish, a course in Race, Political Power in America, an Introduction to Mexican-American Studies and a course from one of the Research Methods list of classes. Then they would continue by pursuing one of two paths. One path required the students to take 4 courses from each section III and IV of the document course which are the list of Humanity and social science courses, respectively. Or if they preferred to develop a specialized skill in a particular area they could take any 4 courses in their area and any 4 courses in the other major section, e.i. 4 in history and 4 in social science. The student had some degree of liberty to what they wanted to take as section III and IV list of 33 classes to chose from.

The final section of the document is more at the administration level. As this section deals with the salary of the Director of the program and cost of the program as a whole.

This document seems to fit the needs of the population but still does not give us much to grasp on as to the change in the demand over the course of 5 years.

Sources:

Loyola University. Bellarmine College Record Group. Mexican-American Studies Degree Program, February 14, 1973. RG 12, Record Series D: Departments and programs, Box 14. Loyola Marymount University Archives, Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, LMU, Los Angeles.

Photo:

Special Collections Entrance, Los Angeles. Personal photograph by Carmen Castañeda. 2012.

Read more:

The Birth of the Chicana/o Studies Department, Setting the Stage, Students Propose a New Program, Capstone Project Gone Blog, So You Want to Take Introduction to Chicana/o Studies?, So Let’s Put Some of the Pieces Together