The Center for Service and Action at LMU offers opportunities for students to volunteer throughout the year; one of these opportunities is the range of Alternative Breaks for the winter, spring and summer. I participated in the Alternative Break to Florida this past winter that focused on becoming more aware about the Immokalee field workers working and living conditions as well as their involvement with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) non-profit organization. The group was composed of 14 participants, including staff and students. We learned a little bit more about the work that the CIW has accomplished, and the resources available to the children of the field workers.

Immokalee and the southwest of Florida is significant to the agricultural production fabricated by approximately 4,000 members of the CIW who travel throughout the East coast during the harvest season. These are hard working immigrants that mostly come from Mexico, Central America and Haiti. The CIW fights against the injustices they face in the tomato and citrus fields where they suffer from extremely low wages; and are deprived of sanitary living conditions as well as their human rights. Just like textile workers were paid by the piece, tomato field workers are paid by the bucket — for every 32 lbs. of tomatoes they pick they are paid $0.50. In our orientation meeting with some of the leaders of the CIW we were asked to pick up a 32 lbs. bucket to get an idea of how much that weighs. I can only imagine what it must feel like to work out in the freezing winter / hot summer fields. The majority of the field workers are men, although there is a small percentage of women who are also field workers.

The CIW began by organizing weekly meetings in a room provided by a local church in 1993. The group became more aware of their deprivations as human beings and six of the members went on a hunger strike that lasted one month in 1998. The CIW stated that by 1998, they “had won industry-wide raises of 13-25% (translating into several million dollars annually for the community in increased wages) and a new-found political and social respect from the outside world” (in About the CIW pamphlet). Through the support of students and organizers, in 2000 they marched from Ft. Myers to Orlando, a 234 mile march.

In 2001 the CIW held a national boycott for Taco Bell in which university students joined “Boot the Bell” from their campuses and demand the giant to take responsibility in promoting the enforcement of human rights in the fields where its produce is grown and picked. It took Taco Bell five years to finally agree upon the four demands to act socially responsible and improve field worker’s wages by paying $0.01 more per every pound of tomatoes it purchases from the growers. In April 2007 McDonald’s agreed to work closely with the CIW and investigate cases of abuse in the fields. In 2008 Burger King and Subway joined the promise to ensuring the workers would earn $0.01 per every pound of tomato they pick.

Much of the reason why our group wanted to know more about this issue is because Trader Joe’s, a major tomato consumer, had been reluctant to signed off the Fair Food Agreement. We have a Trader Joe’s within a distance of LMU and many of the student body goes there to purchase their groceries. Coming back from the trip as a group we wanted to protest outside of the Trader Joe’s and urge them to sign off the Fair Food program. But in February of this year Trader Joe’s demonstrated its support and its promise to a sustainable tomato industry for field worker’s and their human rights.

In 2008 the CIW assisted with the investigation of an indenture servitude slavery case where Cesar and Geovanni Navarrete were sentenced to 12 years in federal prison for depriving 28 field workers of their rights and holding them hostage. Above are some pictures showing the place were the trailer use to be. The employers placed the workers under high surveillance and instigated fear so that they would never dare to leave the campsite. In one instance the employers took the workers to the nearby grocery store and two of the workers took courage and managed to escape the store and run to ask for help. The CIW helped with the investigation of this case and as a result the two employers were sentenced to federal prison. Through the CIW’s activism in investigating seven cases of modern day slavery, the CIW has helped to liberate 1,000 workers.

Last week on March 25, 2012 a man walked into the CIW’s office explaining what had just happened to him at his job. He was working at the vegetable packing house, packing eggplants, when the supervisor came up to him and began criticizing his work. The worker felt this was unjust so he talked back; the furious supervisor punched him in the face breaking his nose.

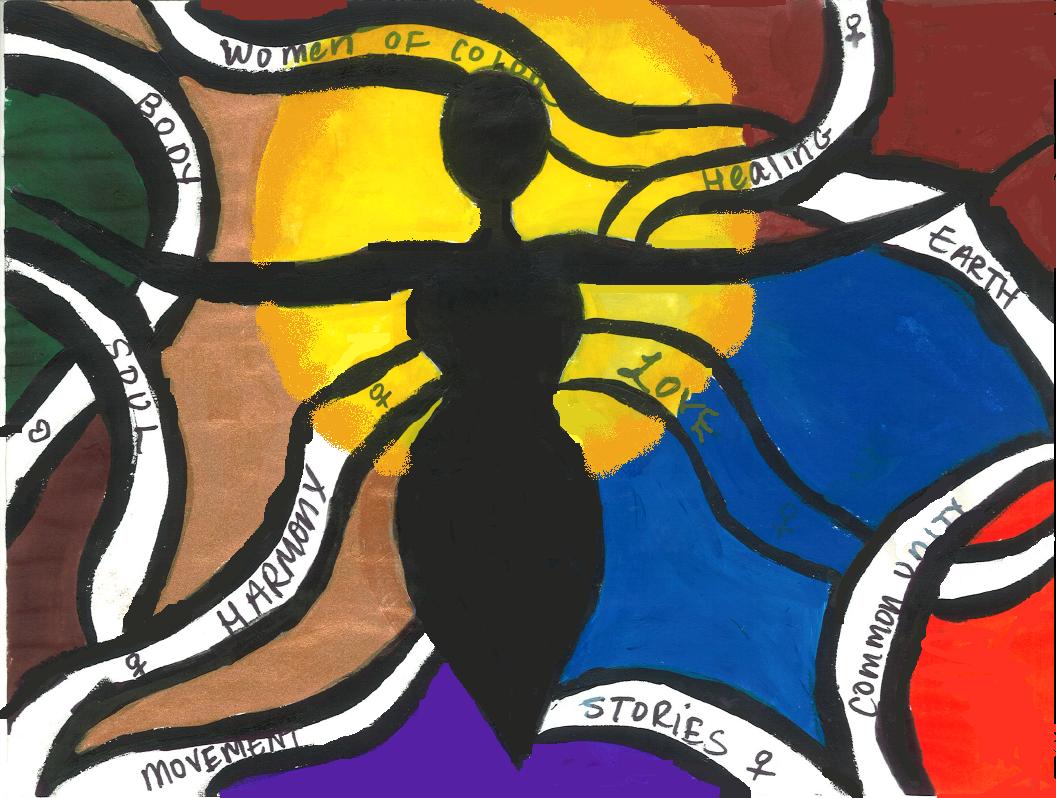

Why am I writing about this under a Chicana Feminisms blog space? Because this demonstrates yet another form of marginalization towards the Latino community. Women make up a small percentage of immigrant field workers in Immokalee, but they certainly are present. They get up early every morning, take care of household arrangements and get ready for the day’s field work. The deprivation of human rights and the modern day slavery cases that victimize field workers who come to this country to better their conditions continues to be a reality. We can become more aware of these injustices and promote change for social justice. Exposing myself to these kinds of experiences makes me more aware of the problems we need to change in our society. The poor, the immigrant, the minority, continue to be marginalized under the system of domination. This is a call to everyone who stands for social justice to seek justice by becoming educated and acting against the constant forms of oppression.

Visiting the town and specifically meeting the soccer coach, Manny Touron, from Redlands Christian Migrant Academy made me happy to know that there is people out there who believe in their students and who dedicate time to guide them to succeed. Manny coaches boys in soccer through an after school soccer academy. One of the things that deeply touch me was when a boy from the team shared with us that the thing that saddened him the most was the fact that he sees his friends more than he sees his parents. This young boy, as well as the rest of the boys have dreams to fulfill, visions to live, and amongst those dreams are providing a stable future to their families through education. Manny dedicates his time to these children; he doesn’t get paid much, but he absolutely loves what he does.

For a virtual tour of Immokalee please click this link: http://ciw-online.org/virtualtour.html

Additional Sources:

- http://www.naplesnews.com/news/2012/feb/09/trader-joes-coalition-of-immokalee-workers-agree/

- http://www.ciw-online.org/index.html

- http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/02/10/trader-joes-fair-food-agreement_n_1268417.html

- http://www.ciw-online.org/about.html

- http://www.traderjoes.com/about/customer-updates-responses.asp?i=60

- Student Farmworker Alliance: http://www.sfalliance.org/

- http://www.alternet.org/newsandviews/article/778484/finally!_trader_joe’s_signs_on_to_fair_food_agreement_for_farm_workers/

- “The more things change?…” http://ciw-online.org/not_1996_anymore.html