Lorna Dee Cervantes is known as one of the greatest poets in Chicana literature. She was born on August 6, 1954 in San Francisco, California. Her parents came from Mexican and Native American descent. When she was young, her parents divorced and her mother took her and her brother to San Jose, California to live with her mother. Cervantes had a tough childhood living in a neighborhood filled with poverty, gangs, and violence. However, she found comfort in writing poetry; at the age of 8 she composed her first poem (Women’s History).

Lorna Dee Cervantes is known as one of the greatest poets in Chicana literature. She was born on August 6, 1954 in San Francisco, California. Her parents came from Mexican and Native American descent. When she was young, her parents divorced and her mother took her and her brother to San Jose, California to live with her mother. Cervantes had a tough childhood living in a neighborhood filled with poverty, gangs, and violence. However, she found comfort in writing poetry; at the age of 8 she composed her first poem (Women’s History).

During her teenage years, she was influenced by African American women poets and reading their poems “politicized her.” She started questioning the dynamics of oppression, especially of women, and this made her very angry. Cervantes went on to work as an activist for the National Organization for Women, the Native American Movement, and the Chicano Movement. She used her poetry as a “weapon to denounce racism, sexism, violence against women, and the oppression of the disempowered” (Gonzalez). Later on in life, she went on to publish three books of poems: Emplumada, From the Cables of Genocide: Poems on Love and Hunger, and Drive: The First Quartet.

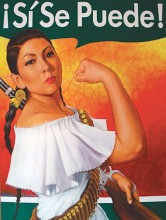

In 1975, Cervantes wrote the poem Para Un Revolucionario [For a Revolutionay]. The following is my own interpretation of what she is trying to tell us in this poem. Given by the title, it is evident that this poem is directed toward the Chicano (men) on behalf of the Chicanas. She begins by describing that the words of liberation spoken by the Chicanos are like snow and the warmth of sun. Their Chicano spirit is so high that no army, police, or city can bring them down. His persuasive words draw her in and the “snow” raining from his mouth covers her breasts and hair. This can be a reference to how the men in the movement tried to get the young women to sleep with them. In Blackwell’s, Chicana Power, she mentions “sexual politics” and how men used Chicanismo to get women into bed.

In the second half of the poem, the tone changes the Chicana is bothered by the fact that she is stuck in the kitchen cooking and cleaning while he’s in the living room spreading his dream to brothers. This represents the sexism in the movement. Women we not allowed to discuss their opinions and ideas and if they did, they would be ignored and not taken seriously. The women did the “work” in the movement the cooking, cleaning, and typing. The poem goes on to say, “Pero, it seems I can only touch you/ With my body.” Once again, this describes how Chicanas were seen as sexual objects and not as political comrades and the only way they paid attention to the women were for sexual favors.

At the end, she addresses the “hermano raza” with her fears. “I am afraid that you will lie with me/ And awaken too late/ To find that you have fallen.” She is warning the brother raza that the revolution will fail without the cooperation and equality of Chicanos and Chicanas in the movement.

References

Blackwell, Maylei. Chicana Power!: Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement Austin: University of Texas, 2011. 70-76. Print.

Garcia, Alma M. “Para Un Revolucionario [For a Revolutionay].” Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings. New York: Routledge, 1997. 74-75. Print.

Gonzalez, Sonia V. “Poetry Saved My Life: An Interview with Lorna Dee Cervantes.” Goliath: Business Knowledge On Demand. MELUS, 22 Mar. 2007. Web. 30 Jan. 2012. http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-7647816/Poetry-saved-my-life-an.html.

“Women’s History – Lorna Dee Cervantes.” Gale Cengage Learning. Web. 30 Jan. 2012. http://www.gale.cengage.com/free_resources/whm/bio/cervantes_l.html.

Photo (image): http://www.poetscoop.org/SPRING2010BIOS.htm

Reading Assignment: Your reply (under Comments) is due before class on Wednesday, February 1. Remember, you don’t need to answer all or even any of the questions, but your response should demonstrate you’ve done and thought about the readings. Be sure to check and make sure your response posts.

Reading Assignment: Your reply (under Comments) is due before class on Wednesday, February 1. Remember, you don’t need to answer all or even any of the questions, but your response should demonstrate you’ve done and thought about the readings. Be sure to check and make sure your response posts.