https://citedatthecrossroads.net/chs486/2016/10/08/the-altar-process/

The altar is for mi familia which includes individuals who are not blood-related. The altar is a reflection of my multigenerational family ranging from my great-great-grandparents in Mexico to my young cousins. The important value that derives from my family is that it is not just about the family but it is a reflection of the individuals and their impact on my life, either directly or indirectly. A mix of patriarchal and matriarchal families has developed different components that have molded the person I am today. There are calaveras placed in the center of the altar with the family names for all three family ties: Alejandre, Carrillo, and Serna. From my great-great-grandparents to my family dog, each is important and have marked my mind and soul. Their influences have created numerous values – faith, optimism, courage, determination, taking action and the importance of friends and family.

The focus of my altar are photos of my great-great-grandpa, great-grandma, grandfather and aunt Esther. They display the transition of authority between genders, as all four were the head of the household, including the women. The breaking of traditional gender roles began before my birth, as the women in my family had become homeowners in the early part of the twentieth century. For Mexican women to acquire property in the United States without male authority and who spoke only Spanish, is astonishing to me. The unfathomable obstacles and prejudices they must have endured to acquire property are an inspiration. My great-grandmother’s strength and perseverance to obtain her property is an example of a strong-independent woman. My grandfathers were both respectful and hard-working individuals and they are the source of my work ethic.

My grandfather Luis was diagnosed with lung cancer and within a year he lost his battle and passed. One of the items on the altar are the last pack of cigarettes that my grandfather had, he had continued to smoke after his diagnosis. My grandfather enjoyed his cigarette breaks, it was his alone time from the chaos of a full household. The cigarette pack reminds me of my grandfather sitting on the porch and the conversations we had for that brief moment. He would wear his Kangol hat, a light jacket, while enjoying a cigarette. We would the most interesting conversations because my spanish was improper yet I understood most words and my grandfather had broken english but understood it perfectly. I always joked with my grandfather and he genuinely showed how proud he was of us, he saw the importance of education through our eyes. I am determined to break through barriers just as they did coming from Mexico with nothing but hope and determination to establish a strong foundation for future generations.

Along with these successes my family has endured great sadness and hardships. Two such losses were loss of my toddler cousin DJ and stillbirth of my cousin Mila Rose. Their lives were a contributing factor in retaining my faith. Their significance to the altar is as a reminder to not take life for granted and that in due time, a better understanding and perspective will arise. My cousin DJ was born with complications that resulted in cerebral palsy and he was admitted to the Los Angeles Children’s Hospital numerous times. His complications were uncommon and it was hard for the doctors to give an exact diagnosis or life expectancy. A couple months before his death, DJ time was limited. His health declined and we said our “goodbyes,” yet when they removed all of the tubes and IVs that stabilized him, he fought hard and survived. The doctors were speechless at his strength and he lived an additional 3 months peacefully. The death of DJ has allowed our family to give life back, by having an annual blood drive at the Los Angeles Children’s Hospital. We continue to celebrate his life by giving life to children in need of blood donations.

There are a few photographs of younger individuals, for example, my friends Jessie, Jacob, Salvador, and Ashlee, were all around my age when they passed away tragically. During my senior year in high school, my brother’s two childhood friends were brutally killed at the house party in Eagle Rock. My brother Jesse attended elementary with both of them creating a solid bond between them. During high school, we took kick-boxing classes together and there was always joking and laughter going on. Jacob went to a different high school than us but he always kept in contact with “the guys” periodically. Jacob was a jokester and he would play endless pranks on everyone, his free spirit and humorous attitude was refreshing. Jessie was known as “Little Jessie” because of his short stature, he was muscular and from afar he looked serious. Yet when you got to know Jessie he was a flirt with a radiant smile. He adored classic cars and drove a brown El Camino to school. He would give my brother and I rides because we took 3 buses to commute to school. He would be waiting for us in his wife-beater and slick sunglasses, bumping music in the parking lot. He was always smooth with his words and treated me like his little sister.

The night of their deaths, all of the guys from their group of friends were to attend the house party, though, due to various reasons Jessie and Jacob were the only ones from the group who attended the party. The following morning I received a phone call at work from my older sister Donna that “Jesse and Jacob were killed last night,” my heart instantly dropped and my vision became blurry. I immediately thought it was my older brother and got physically ill. When she clarified that it was the boys I was struck with grief and an uncontrollable scream was let out. That pain was indescribable and loss of these two beautiful individuals was unimaginable. At the party, they were caught in the middle of a fight amongst rival gang members and Jacob tried to break it up but was knocked unconscious. Jessie was upset and tried to figure out who had hit Jacob but before they could leave, shots rang out and Jacob and Jessie were killed.

Their funerals were a reflection of their contagious smiles and funny personalities with over 500 people showing up to both services. The endless amount of lives these two touched showed how special they were to not only their family and friends but to the community as a whole. Their deaths were a pivotal moment in our lives, we no longer felt safe going to house parties and we understood the reasoning behind my mother’s “I am not worried about you, I am worried about other people” saying. We learned that their loving and humorous attitudes left a mark on all of our hearts and gave us an example of how to live life.

Tragedy struck again the following year with the death of my close friend Salvador. We had a close relationship throughout high school, as I would encourage him with his studies and help him out with assignments. I saw that he was struggling in certain classes and I wanted to help him succeed, we would go to the library after school, and just talk for hours. He gave off good vibes and we grew closer as the years went by. In 2007 on Easter Day a group of girls had hung out and partied, one of the girls was Salvador’s cousin, Sandra. She received a phone call in the morning from her mother that she had to get picked up immediately. Shortly after she leaves she calls us and told me that Salvador was killed the night before while picking up a friend from a party. Gang members were waiting for his friend outside and they ambushed the two men, shooting both. It felt like deja vu because once again neither of our friends were gang affiliated, but, both of their deaths were a result of gang violence. Losing someone is difficult as is, but not being able to make peace with them is harder.

Last year I lost my friend Ashlee to cancer and it was difficult due to not being on speaking terms prior to her illness. She was a driven hair stylist working in Hollywood at a well-established salon. Ashlee had such a mellow and “always cool” attitude and I met her through mutual friends. One of my fondest moments with Ashlee was bartending at a friend’s party, where we just rolled with it, even with no prior experience. Her nickname was Booji because she was always trendy and working with the latest celebrities, yet, her humble roots shined through. She had a saying “Slauson to Sunset,” which was her motto because she grew up in Mid-city Los Angeles and learned how to do hair from a young age. We had weekend getaways to San Francisco, San Diego, and Palm Springs, we always a good time, she was carefree and always introducing me to new hip hop songs.

We had a dumb fallout and the dynamics of the group friendship shifted as people changed and our paths diverged. I had heard from mutual friends that Ashlee was not feeling well. A few months later, news broke that she had lymphoma cancer and was set on a holistic treatment and when that failed they began chemo. I had thought numerous times to reach out but I couldn’t. Her progression in treatment seemed to be going well until she got an infection after one of her treatments. One of our friends reached out and told me she was not doing well and that she needed a ride to see Ashlee. I didn’t hesitate because regardless of not having spoken to her in months, I loved and cared about her. To see a friend, so young, in that situation is devastating and it challenged my faith. I was so distraught at the fact of how healthy and young she was the year prior. I spoke to Ashlee and asked her for forgiveness, I saw her eyes open but we never spoke. I had to make my peace with her and that experience has changed me on reacting to certain situations. I put my pride aside and accepted all my flaws to face the reality and say my goodbyes. Ashlee was an independent, focused, and successful woman in the short time she was on this earth. She displayed courage, humility, and was willing to try new things and see new places.

Their sudden deaths and their inclusion in the altar represent one of the hardest times for myself and my family, yet despite these hardships we are reminded that we overcome these tragedies of lives being suddenly “cut-short” together. These friend’s attitude on the life of “living freely” have had a lasting impression on everyone. They all displayed courage during their fight for life and instill in me, a continuous fight in making a positive impact on those around me. Their young souls made a great impact on everyone they encountered and it would be nice to uphold those qualities.

There are numerous photographs from all three sides of my family represented on the altar. The person I hold a special bond with is my Uncle Teo. He was my nino (godfather) and he played a significant role in my life by filling the void my father created. We all lived on the same family property and daily interaction with him were normal. He would show us his Harley Davidson, his cars and he would wear cologne and he’d also show up wearing his cool sunglasses. He was the life of the party and would always make sure everyone was entertained. Anytime I needed something; from a ride to work or those unwanted discussions about my attitude, he fulfilled that male role model authority and stability for me.

My most vivid moments with my uncle would be his car rides because he would have the corridos while driving down Brentwood, a predominately white neighborhood – he didn’t care. He would drive his truck with the windows rolled down just to make sure every passing person and car heard his music. He would tell me that I should be proud of being brown and never downplay my Chicana culture and traditions. After he passed, my aunt gave me a few of my uncles personal items and she had found a jar with some used joints. That jar is now displayed on my altar as a reminder of my uncle’s youth days. Lastly, the songs that he would listen to, I never paid much attention to, but following his unexpected death, I realized most of them had much deeper meaning. Songs from Ramon Ayala, Los Tigres del Norte, and other corridos are meaningful ballads that speak about life and death and about embracing each and every moment while we are alive. They are all an influence on my outlook on life, to appreciating the small moments, just as much as the big moments.

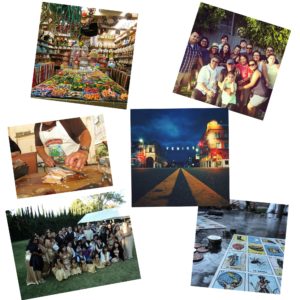

The altar represents the four essential components of nature; wind, earth, water and fire. To represent wind, I have displayed bright and bold colors of papel picado draping around the altar like a picture frame. The papel picado is a thinly cut paper and the art displays muertos or religious images. The papel picado moves freely through the breeze and it outlines the entire altar. The miniature clay pots and bowls that hold salt and vegetables are symbolizing the earth. Some of the miniature food products display plates of mole, a traditional meal that is left for the souls to enjoy. Water is placed in the miniature clay pots and illustrates the purification of the souls and the water refreshing the soul’s thirst. The placements of orange, yellow, and purple cempazuchitl (marigolds) bring life to the altar along with a strong scent. The Mexican sombreros are put on various picture frames to illustrate our Mexican pride despite our American upbringing. The photographs are mostly prints but some are so old that they are physically painted and it adds a special touch to the altar. There are numerous candles lit during the night and it illuminated the pictures. All of these different aspects are a representation of my family members and their contributions to my entire existence.

Work Cited:

“The Day of the Dead.” 2016. Accessed December 1. http://www.unm.edu/~htafoya/dayofthedead.html.

“Dia de Los Muertos Celebrations Bring Ancestors, Traditions back to Life | Daily Bruin.” 2016. Accessed December 1. http://dailybruin.com/2016/11/01/dia-de-los-muertos-celebrations-bring-ancestors-traditions-back-to-life/.

Rodríguez, Richard T.. Latin America Otherwise : Next of Kin : The Family in Chicano/a Cultural Politics. Durham, US: Duke University Press Books, 2010. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 1 December 2016.