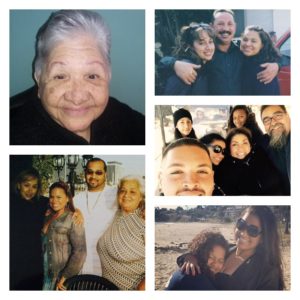

My family photo collage depicts photos of my grandma (first upper left picture), mom (second picture under my grandmother- she is to the far right with gray hair), dad (he is in the photo directly to the right of my grandmother with my sister on the left, my dad in the middle, and me to the right-he is hugging us), older brother (he is in the bottom left hand picture under my grandma’s picture in the center wearing white standing in between myself and mother) little sister (in picture to the left of my dad and in the second picture under my grandmother-she is first in pic from left to right wearing black with blonde hair), daughter (last picture at the bottom far right leaning her head on me), little brother (he is the first face in the photo above my daughter and me), step-mom and step dad (they are both in the same photo as my little brother- step mom in the center wearing black in between me and my her husband, the one to with the beard and glasses).

From birth to the age of nine, I grew up with two parents in the home. My family consisted of a heteropatriarchal structure with my father at the center. My father is Greek, while my mother is Mexican, so the Spanish language was not spoken in the home. With that being said, we didn’t identify as a Chicano family, however, many of the patriarchal traditions (heterosexuality, masculinity, machismo, domesticity-rigid sociocultural traditions and expectations) persisted in our day-to-day life. Although “Historically, in dual headed households, Chicanas (as well as other women) were relegated to the tasks of homecare and child rearing, while the men took the task of earning the families income” (Trujillo, 190), my family structure differed. My mom had added responsibilities, “the true backbone of the familia” (Trujillo, 189). Both parents were breadwinners; we were a middle class family. My dad was a plumber, and my mother held a white-collar position as supervision at a cake-designing factory in Marina Del Rey, California. We even had a dog, Molly-some thought we were living the American Dream-money, home with a white picket fence, nuclear family with two parents and one boy and two girls, with a male at the center, my dad. In terms of gender roles and expectations, my mother held all the female traditional roles associated with domesticity such as cooking, cleaning, and making sure that my siblings and I, were taken care of. My dad was the patriarch and disciplinarian, who used force when necessary- yes, he used the “belt” on us a few times when we were kids.

A typical day of my life during that time went like this; we wake up, my mom made breakfast, and we all sat at the breakfast table and ate. Of course, my dad the patriarch was the first person, who my mom served at the breakfast table. And, we had to wait until everyone was sitting before we could start eating our meal. We were expected to eat everything on our plate. After breakfast my dad would grab his home-cooked lunch that my mom made the night before, hop in his work truck and hit the road. After asking if we could be excused from the breakfast table, my sis and I would help my mom clear the dining room table and clean the kitchen. While we cleaned up, my older brother would put our backpacks in the car and warm up my mom’s car. After a long day at school, my mom picked my brother, sister, and me up from my grandma’s house-she watched us afterschool. My grandmother (she is in the center of my collage cutting onions), who came to the United States in the late 1940’s, is very traditional-she has adopted the gender norms that reinforce patriarchy in Chicano families. Her life revolved around my grandpa, 10 kids (7 boys and 3 girls), and maintenance of the home. Once she met my grandpa, who passed away when I was two, she took on the stereotypical roles of Mexicanas-the “good wife and mother,” relegated to the domestic sphere, “the backbone of the familia” (Trujillo, 189). Once we got home, my mom started cooking dinner, while my siblings and I did our homework. My sis and I always set the table, so that when my dad came home all my mom had to do was serve our plates. Of course, my dad would not sit at the dinner table until after my brother, myself, or sister would take off his work boots. He literally sat in a recliner chair, while one of us took off his work boots and put them on the front porch. Once my dad sat at the dinner table, my mom would serve him first and we would all eat together. We could not get up from the dinner table without asking to be excused. Life, in our home, at least from what everyone thought, was great. However, my dad’s drinking and drug abuse got so bad that he would come home after work drunk off his ass, excuse my French, and beat my mother. His “machismo, and hyper masculinity, rooted in patriarchy,” (Rodriguez) was out of control. The domestic violence, which consisted of emotional, physical, and verbal abuse, began to get worst. But, because we are “taught to undervalue our needs and voices…and that our opinions, viewpoints, and expertise are considered secondary to those of males” (Trujillo, 192), my mom stayed for the sake of keeping the family together-this perfect little family, in the eyes of others. However, after years of abuse, and finally challenging the patriarchy, she packed up with 3 kids, and never looked back.

By this time I was 9; I had witnessed some pretty heavy stuff for a young child. But, I quickly adjusted to my new family structure, a single parent home. There wasn’t that much adjusting to do except for the fact that my dad’s income was no longer financing our middle class life. We downsized, in terms of our lifestyle, and my mom took on most of the financial responsibilities. But, my sister, brother, and I didn’t mind downsizing. As long as my mom wasn’t getting beat every other weekend, we were all happy. As a single mother my mom sacrificed everything for our happiness-we never went without- “her strength and self sacrifice kept the family going” (Trujillo, 189). She made sure that we had the newest toys, clothes, and most of all, love and support. She attended our baseball and softball games, and never missed our open houses, or parent conferences. However, as my mom took on more and more responsibilities at work, she put my older brother at the center of our household, the patriarch. He was in charge of my sister and I until my mother got home from work. By this time, my sister and I had to make sure our homework was done, along with dinner. My brother’s only responsibility was to take out the trash. We cleaned and did the laundry, his included. Of course, due to his gender, my mom never made him do any housework-neither would my grandmother. Our family adopted the Chicano family structure with the male at the center, a very patriarchal system relegating women to domesticity, giving males the power and control, dominating the family landscape-something that Rodriguez addresses in his book.

As time went on, my mom and dad remarried, so I experienced the step-dad and step-mom family dynamics too. The family structure of the home was still patriarchal, with males at the center-catered to, while the women, my mom and step-mom, held fulltime jobs, in addition to maintaining the responsibilities of the home and children. Not much changed in terms of family dynamics, we couldn’t “Shoot the Patriarchy,” something Rodriguez discusses in his book. Today, my mom and dad are single, and have not remarried. I still have a wonderful bond with my step-mom, my dad’s ex wife, and her new husband. Although most part of my life, I have been conditioned to take on gendered sociocultural traditions that are oppressive, I have been exposed to a more egalitarian family structure. My step-mom and her new husband have stepped away from the patriarchal nature of the Chicano family structure. In their household, they both maintain full time employment; however, when it comes to the domestic sphere, they maintain an egalitarian household. Both of them take turns cooking and cleaning, so they have moved way from the traditional gender roles and expectations. Because he cooks or does laundry, it does not take away from his manhood or masculinity. They do not let the rigid gender roles define the structure of their marriage, family, and home. My little brother has to be one of the best house cleaners in Carson, California. My step mom definitely taught him that he is responsible to help around the house, too (he vacuums, does dishes, laundry, etc.). What they have done is “Shot the patriarchy.” They have moved away from patriarchy, which informs our societal and familial structures, something Rodriguez points out in our book.

In terms of my family structure, it is a heterosexual single parent household-just my daughter and I. Her father is there financially, however, he is not consistent physically or emotionally. Considering this, I feel like I have to be extra influential when it comes to raising my daughter’s feminist conscious. I refuse for her to be a “passive victim of the cultural onslaught of social control…that socializes women to be the good wife or that she is incomplete if she doesn’t become a mother” (Trujillo, 189). Thankfully, I am an educated Chicana feminist and work daily to decolonize my mind. As a result, I am able to give my daughter the tools to help her challenge the patriarchal structure of our society, which perpetuates interlocking systems of oppression (sexism, classism, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia). I am raising my daughter in a way that she will be strong and independent-not a woman who will conform to, and reinforce societal and familial sociocultural traditions and expectations that oppress women. She has already challenged sexist hegemonic ideals, rooted in patriarchy. For example, she and her friends have organized around the issues of the female body directly associated with the dress code at school. Although the dress code still persists, and they can’t wear certain types of blouses, she proved to me that she has already developed a feminist conscious exercising her right to freedom of expression when it comes to the female body and clothing. Already, she demonstrates that she is an agent of the self, and challenges the status quo- my little political feminista.

Needless to say, across time and space, family dynamics change-they are not static, or universal, as Rodriguez points out in his book. Also, gender is not static. Women and men should not be relegated to binary constructs that perpetuate the male/female dichotomy, with rigid gendered characteristics and roles they must ascribe to (male=patriarch and masculine/women=domestic care take who is feminine). We do not have to live by socially ascribed societal and familial traditions and beliefs. We must create a society, which allows people to construct their own reality when it comes to the family unit. We must do away with heteropatriarchy if we want to live by democratic principles, which consist of equality for all.

Lovely collage, lovely blog post.